Nearly 40% of land use across the globe is dedicated to one thing: agriculture. So, it makes sense that an equally large amount of our natural resources, freshwater in particular, is also dedicated to agriculture and crop growth. Agriculture has been the source of some of humankind’s most defining inventions and innovations, changing entire societies and the course of human history. That’s no small thing.

With that in mind, it should come as no surprise that how we implement agricultural practices is no small thing either. Agriculture has an enormous impact on our environment, from the methods we use to plant and harvest crops to deciding if chemicals and compounds are to be used to keep them pest-free while growing. If we want to address the climate crisis, we must address agriculture—one of the top five sectors contributing to pollution and carbon emissions today.

But it’s certainly easier said than done. After all, “agriculture” is inclusive of a cornucopia of ideas and practices, covering everything from soil health to land management for livestock, native plant species, freshwater and irrigation practices, and so much more. How can we even begin to address issues within agriculture—especially when it comes to changing practices that have been in place for decades, if not centuries—and on a global scale?

Believe it or not, we need to look backward—to a set of practices and principles that have been utilized by Indigenous communities for thousands of years to protect, steward, and work with the land, not it.

This is regenerative agriculture.

What Do We Mean When We Say “Regenerative” Agriculture?

If you find yourself confusing “regenerative agriculture” with “sustainable agriculture,” you are not alone. Or maybe you’ve never heard of either; that’s okay, too. Just know that these two concepts are frequently used as synonyms for one another when they are often distinctly different.

Sustainable agriculture describes the practice of farmers and other land managers reducing their harm to the planet by swapping current practices (those with damaging side effects for the natural world) with environmentally friendly ones. This can include everything from reducing and eliminating pesticide use to adapting irrigation methods for water conservation.

The added bonus of regenerative farming is exactly what the name suggests: regeneration of the land itself. Regenerative agriculture is practiced when farmers and landowners take steps to replenish the land they live and work on, using both biological and ecological principles to work with the land as a system in the process of yielding a harvest. Key tenets include minimizing soil disruption, utilizing cover crops, rotational grazing, and decreasing inputs from outside the system of cultivation rooted in place to restore soil. As a result, the land produces healthier crops, hosts more animals, stores more carbon and water, and supports greater biodiversity—all without outside inputs like pollutant chemical fertilizers.

A Rich Indigenous History of Regenerative Agriculture

Indigenous and Tribal communities around the world have been practicing the principles of regenerative agriculture for thousands—yes, thousands—of years. While these practices are not all the same, often region and climate-specific, they all stem from one core principle: developing a process that works with the land, focusing on the health and wellbeing of humans and the natural world alike.

One popular example is the “three sisters” planting technique. This is the Native American practice of growing corn (maize), beans, and squash interspersed. Known today as a process called “intercropping” or “companion planting” the beans add nitrogen to the soil—essential for plant health—while the corn acts as a pole for the growing beans. The leaves produced by the squash plants keep the soil cool and moist. Working together, these three crops create ideal growing conditions for one another and enrich the nutrient makeup of the soil as well as holding moisture so less water is required for them to grow.

This is merely one example of regenerative agriculture among many of the practices of Indigenous cultures worldwide. Other notable examples include waffle farming, flood irrigation (using traditional and native crops), no-till farming, agroforestry, and silvopasture.

Check Out This Video from Kiss the Ground to Learn More About the Immense Possibilities of Regeneration

Listening to the Experts

Yet, despite millennia of Indigenous traditional knowledge, Indigenous leaders and those who continue these regenerative practices today are often overlooked, spoken over, or not given a seat at the proverbial (or literal) table. Regenerative practices have the power to change the world for the better and for the long-term, but to do this correctly, we need to give space and resources to the experts. We need to acknowledge that the solution lies with the engagement of Indigenous experts and in diversifying farming systems at large.

But how do we begin?

Overcoming Obstacles

If we are going to successfully implement regenerative agricultural practices at scale, there are a number of obstacles that need to be addressed, including how we work with existing farms and farmers, how resources are distributed to those making these shifts, and how we incentivize this change.

Starting with the food we grow and where we grow it.

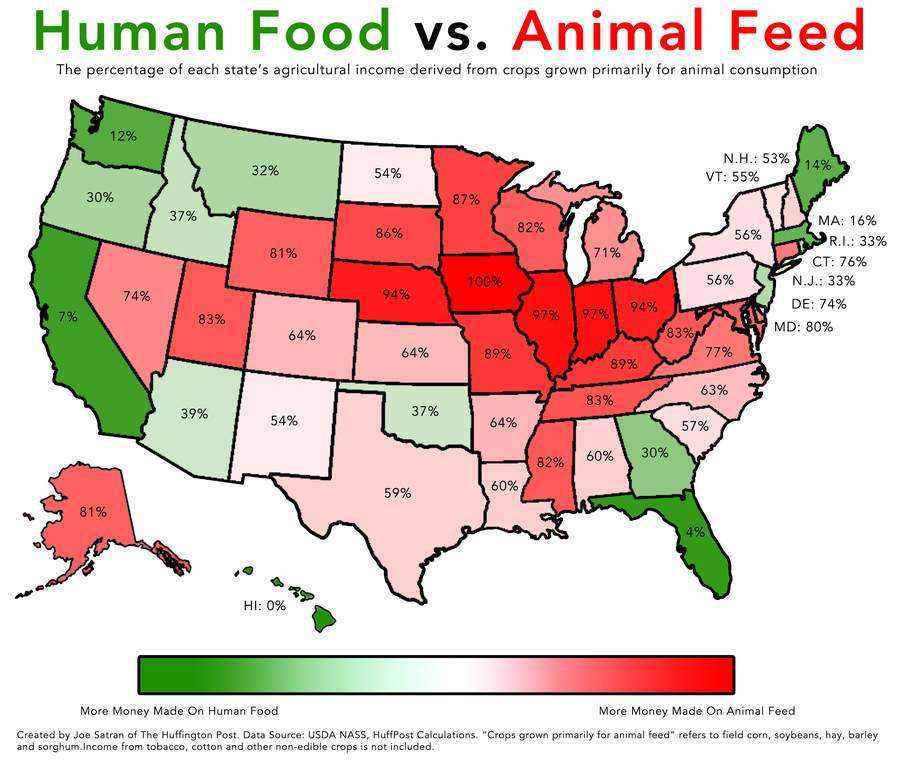

HuffPost produced a map of the United States that shows which states receive the majority of their income from animal feed crops versus crops for human consumption, and the results may surprise you.

States throughout the central-most portions of the U.S. largely produce crops specifically for animal feed (primarily corn) as well as the production of ethanol, a corn-based fuel alternative that is even more carbon-intensive to produce than gasoline. It’s largely costal states—including California, despite its scarcity of freshwater —that produce the majority of crops for human consumption. This means that these crops, grown on the edges of America, have to be shipped throughout the country, garnering an even greater carbon footprint along the way, just to show up at your doorstep. And yet, many of America’s central states are fully capable of growing enough crops to feed the majority of their citizens; crops that are more suited to their climate and natural environments, making them easier and less resource-intensive to grow. There is a clear need to strike a balance; to grow the food we eat closer to home.

To make a change like this, we’re going to need to support farmers. Unfortunately, change on this magnitude doesn’t happen with a wish and the snap of our fingers. Farmers need money, resources, education, and systems of support to be able to implement change at scale. Like any other job, farming is an expertise, and it’s important to remember that, even if it’s of major global significance, asking someone to alter their practices—to learn and implement entirely new skills and techniques—is not a small request; it will need both support and cultural consideration.

It’s also important to note that, as it stands, farming itself is not highly profitable. It is, however, an essential sector for the overall wellness of global civilization. This means that, to make positive change, it’s going to require some economic risk and additional expense. Luckily, a review of regenerative farms conducted by the Ecdysis Foundation found that this initial investment pays off. Crop yields naturally decrease when using regenerative farming methods—something that many see as a major red flag since this, to date, has been the metric used to identify a farm’s success and profitability. However, despite the 29% decrease in crop yields found by the study, these same farms were found to be 78% more profitable than their conventional counterparts, due to lower input costs and access to different markets and diversified revenue streams This huge increase means we can overcome one major obstacle: regenerative farming methods are economically viable.

No One Wins When We Pass the Blame

Whether it’s politicians, farmers, environmentalists, or consumers—no one wins when we play the blame game. It’s easy to point a finger and claim that national and global agriculture is suffering, that people and our planet are suffering, because X person isn’t doing their job properly. But the truth is, if we do not support one another to make the necessary change, we’re only prolonging the suffering of everyone (and doing more damage to our environment at the same time). We must prioritize the evolution toward regenerative agriculture and acknowledge that the transition is likely to be bumpy and imperfect. We need to acknowledge, listen to, and trust in the Indigenous communities with the expertise and wisdom to help implement these solutions on a larger scale, and provide a network of support—including financial support—that farmers are going to need to make this change happen.

We ONLY win when we work together. And we need to start now.