SOLUTION

Forest Restoration

Advancing 30×30 goals by restoring our forests

Created in partnership with

Alliance for the Chesapeake Bay

What is forest restoration?

When we talk about restoration, we’re talking about all activities that help restore a forest to health. Among these activities is forest regeneration, or the renewal of tree cover via new tree growth through natural or artificial means. Although frequently used in tandem with one another, these two terms do not mean the same thing. Rather, regeneration is part of the broader restoration solution.1“What are Forest Restoration and Reforestation?” American Forests ≫

How is restoration achieved? There are a variety of methods and philosophies for creating and maintaining healthy forests. In some instances, simply leaving a forest alone to seed and naturally regenerate over time is enough. In other cases, forests may need extra help—especially those that have been significantly damaged by wildfires, logging, mining, agriculture, and other human activity. In these cases, planting young trees or hand-seeding the forest with a diversity of native species is what is needed to promote healthy regrowth.

Other sustainable forest management practices that can be used in forest restoration efforts include:

- Controlled burning

- Pruning or removing underbrush

- Invasive species control

- Maintaining tree diversity

- Identifying the cause of degradation

Traditional Indigenous Knowledge

The Maori of New Zealand know forests well—they’re a critical part of Maori cultural identity. For centuries, the Maori effectively used fire management practices to promote forest health, travel, horticulture, and sustainable access to critical resources. However, when colonial rule put a stop to these practices, largely due to fear, the forests became primed for disaster. Today, New Zealand is seeing an increase of wildfires throughout the country, and modern attempts at controlled burns, using non-Maori practices, are significantly more likely to contribute to wildfires. These fires not only pose a threat to New Zealand’s forest ecosystems, but to the whole of Maori culture.2“Indigenous Knowledges of forest and biodiversity management,” AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples ≫ (IMAGE: Tane Mahuta/iTravelNZ/Flickr)

Urban Forests

The traditional definition of a forest is one we all know—a large area of dense tree coverage—but what if it could mean something else? What if it already does?

More and more, grassroots organizations are focusing on greening cities by improving tree canopy, the measure of branches and leaves that shade the ground when viewed aerially, through tree planting and the management of green spaces and urban forests. While these areas may not match traditional definitions of a forest, they provide many of the same benefits: carbon capture, shade, heat reduction, and wind barrier effects. When we talk about restoring forests, we cannot forget, ignore, or underestimate the significance of urban forests and their ecosystems.3“Urban Forests,” U.S. Forest Service ≫

Tree-filled Elysian Park covers 600 acres just outside the limits of downtown Los Angeles. (IMAGE: Steve Boland/Flickr)

Forest Restoration and 30x30

Forests cover roughly 31% of all land area on Earth and are home to more than 80% of Earth’s land species (plants, animals, and insects). Tropical forests, like the Amazon, are the most biodiverse biome in the world; home to millions of species and one-quarter of the world’s natural medicines.4“State of the World’s Forests,” Food and Agricultural Organization of the U.N. ≫; “Rainforest,” National Geographic ≫; “Wildlife of the Tropical Rainforests,” National Park Service ≫

So, when we say that we need to conserve 30% of our ecologically significant lands by 2030 to protect biodiversity, it’s safe to say that a huge portion of those lands must include our global forests.

“Trees alleviate flood risk, stabilize stream banks to reduce erosion and sedimentation, filter E. coli and other harmful bacteria, lower water temperature, and provide much-needed habitat and food for native wildlife.”

– Alliance for the Chesapeake Bay

Forest Restoration and Climate Change

Like with all natural systems, climate change is having a significant negative impact on our forests, which is extremely problematic given that forest health is one of the most effective ways we can combat the greenhouse gases in our atmosphere.

Aside from producing the oxygen humans need to survive, forests absorb more than 20 billion tons of carbon dioxide every year. It’s believed that native forest restoration on a global scale—in tandem with grassland and wetland ecosystems—could deliver up to one-third of the carbon capture we need by 2030 to prevent the worst effects of climate change.5“Natural Climate Solutions,” Nature Conservancy ≫

But that won’t happen if we don’t immediately begin large-scale restoration and the reduction of harmful stressors like deforestation due to agriculture and mining, pollution, and unmanaged recreation. These practices make forests less resilient to extreme temperatures, changes in precipitation, and natural disasters like wildfires—all threats that are increasingly more common due to climate change.6“Our Forests and Climate Change,” Alliance for the Chesapeake Bay ≫

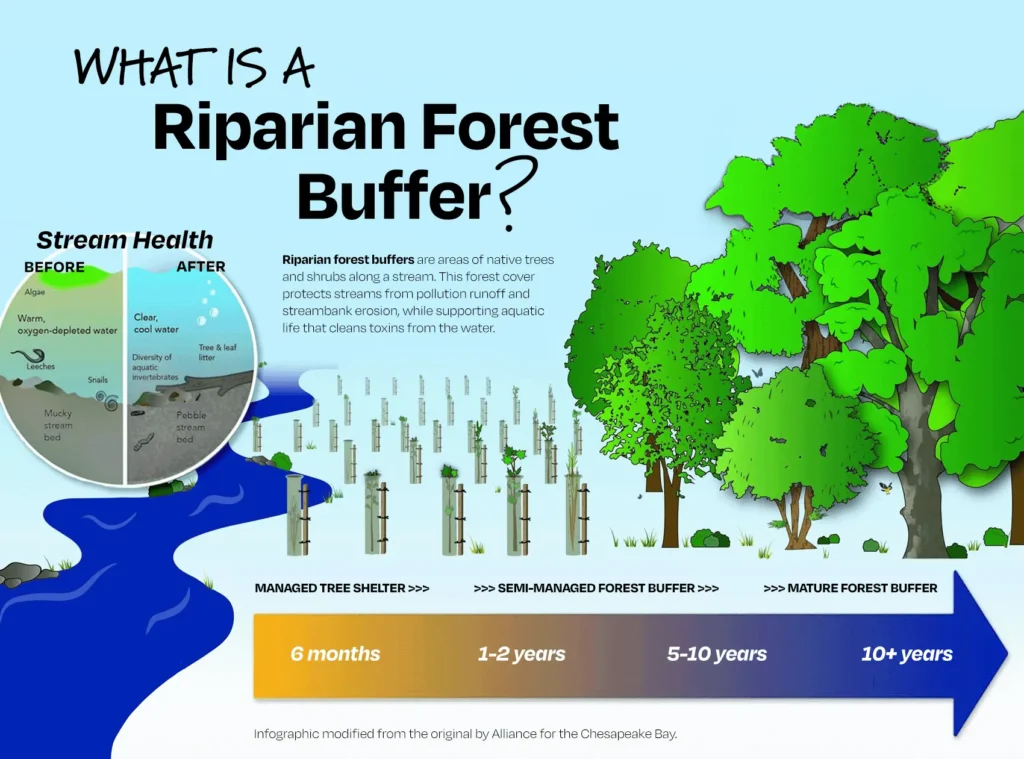

Forests and Our Water Supply

Less obvious is the role our forests play in protecting our waters, too. Not only do trees act as a natural filtration system, but their roots help stabilize the banks of rivers, streams, and lakes, preventing erosion and sediment dispersal and supporting greater aquatic biodiversity. Click to expand the above graphic to learn about riparian forest buffers*Riparian means “streamside” in Latin.and their importance for clean freshwater.7“Importance of Buffer Maintenance,” Alliance for the Chesapeake Bay ≫

Forest Restoration: The Low Down

Learn about the who, where, and when of leveraging forest restoration for 30×30 goals.

- The Who

- The Where

- The When

Trees are everywhere, and with forests covering such a substantial amount of land on Earth, how do we begin to determine who is responsible for taking care of them?

Since we all rely on trees, the “simple” answer is to share the responsibility. While we all must consider how our everyday behaviors influence the world, the reality isn’t as straightforward as everyone doing their part. The greatest responsibility falls to those with an outsized impact on our forests and those with the ability to instigate immediate, widespread positive change. They’re often one and the same:

Once a major industrial zone for early-19th century Philadelphia, today’s Wissahickon Valley Park protects more than 2,000 acres of public woodland in the heart of the city. (IMAGE: Marti C Photography/Flickr)

Except for Antarctica, rainforests exist on every single continent, and more than half of all global forests are located in just five countries: Russia, Brazil, Canada, China, and the U.S. But are these the only places in which forest restoration can be successful? While these countries have a greater responsibility for managing forests within their borders, let’s where forest restoration will have the most impact.8“A fresh perspective Global Forest Resources Assessment 2020,” U.N. Food and Agricultural Organization ≫

Less Developed Regions | In forested areas currently untouched by human activity and development, and where there is less opportunity for agriculture and industry (two of the biggest contributors to deforestation), we need to support sustainable forest management practices. This is the “low-hanging fruit” of forest restoration, easily achievable with limited barriers to entry, and a goal that can be accomplished through the adoption of strong, forest-first policy and legislation.

Agricultural Settings | Agriculture is one of the biggest contributors to deforestation. Millions of acres are cut down every year to make room for livestock and to grow the crops that feed them. For years, demand for increasing beef production has been the number one source of global rainforest deforestation. This is simply not sustainable. To tackle this head-on, we must address meat consumption itself (a more plant-based diet is frequently recommended, noting that this takes time and has many cultural considerations).9“What Are the Biggest Drivers of Tropical Deforestation,” World Wildlife Fund ≫; “How to transition to reduced-meat diets that benefit people and the planet,” Science of the Total Environment ≫

Additionally, sustainable agricultural practices can support healthy forests and animals.10“Mapping global forest regeneration,” Environmental Research Letters ≫ or example, silvopasture is an ancient practice that interweaves both livestock and forest management. Integrating forest restoration into current agricultural land use is a game changer for mitigating climate change.

Urban Settings | There are plenty of well-established statistics on the fall of asthma rates when tree canopy is restored in urban areas, but that’s certainly not the only benefit. Trees also provide crucial shade and have been shown to decrease city temperatures by nearly three degrees Fahrenheit. A recent study also found a direct correlation between increasing urban green spaces and decreasing crime rates. Restoring urban forests (and establishing brand new ones) can have a significantly positive impact on urban communities that are so frequently ostracized from the benefits of trees. These spaces offer a place for rest, connectivity, outdoor recreation, and even access to fresh food.11“Children living in areas with more street trees have lower prevalence of asthma,” Journal of Epidemiol Community Health ≫; “Using Trees and Vegetation to Reduce Heat Islands,” U.S. Environmental Protection Agency ≫; “How Greening Communities Can Reduce Violence And Promote Health,” National Environmental Education Foundation ≫

Suburban Settings | Old, inactive golf courses and abandoned farm fields are great locations for reintroducing forests into suburban landscapes. By taking already-existing plots of land that no longer serve their original purpose and simply adding trees, we can support new habitats and more diverse green spaces in our ever-growing suburban settings.

Another popular approach to “re-greening” our suburbs is lawn rewilding. From seeding pollinator-friendly grass alternatives to planting rows of new trees, what a lawn is and how we traditionally define it has begun to change in recent years.

How long it will take for reforestation solutions to take effect depends on how quickly, efficiently, and widespread we put them in place. Trees take time to mature and grow, and likewise, forest systems need time to recover after damage. A forest left alone without human intervention takes approximately 10 years to recover soil fertility, 25 years to establish a full ecosystem, and up to 60 years for full biodiversity and forest structure to return.12“Study suggests tropical forests can regenerate naturally — if we let them,” Mongabay ≫

But… 2030 is less than 10 years away. Are we hopeless? No! Old, mature forests provide the most carbon storage; however, young forests have shown to more rapidly absorb carbon as they grow. What does this mean? We need a balance between new and old growth.13“How Forests Store Carbon,” Penn State Extension ≫

With human intervention, processes like seeding can occur much faster, taking only weeks or months to accomplish as opposed to years in a completely natural setting. But we need to go big with our restoration efforts—and quickly.14“Reforestation Beyond the Trees,” National Forest Foundation ≫

Volunteers tie up young trees in a forest in Ecuador, part of an effort to support new growth. (IMAGE: Peace Corps/Flickr)

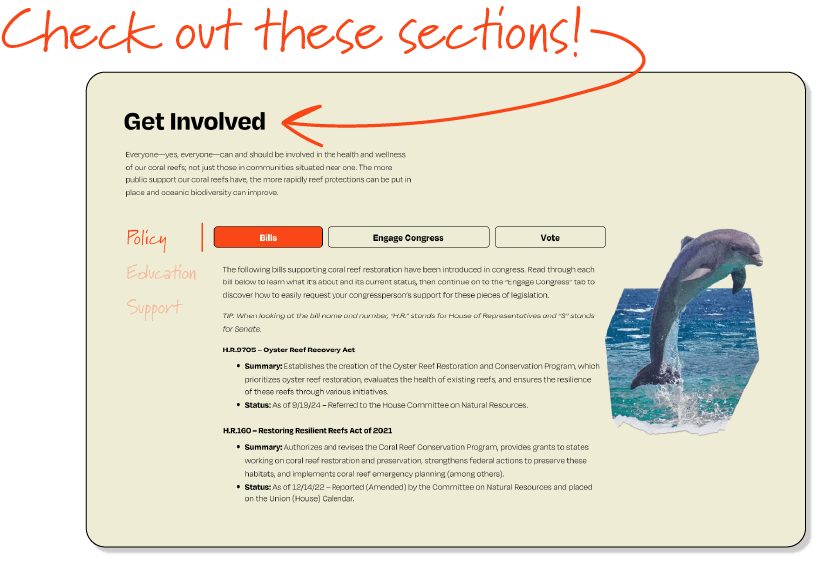

Get Involved

EVERYONE can help to protect and restore our forests, and strong public support is one of the fastest ways to set change in motion, especially in the face of significant obstacles created by rapidly changing federal policy.

Explore below to learn more!

- Policy

- Education

- Support

- Bills

- Engage Congress

- Vote

The following bills supporting open spaces have been introduced in congress. Read through each bill below to learn what it’s about and its current status, then continue on to the “Engage Congress” tab to discover how to easily request your congressperson’s support for these pieces of legislation. (When looking at the bill name and number, “H.R.” stands for House of Representatives and “S” stands for Senate.)

- Summary: Prohibits the importation of products made in whole or in part from materials produced on land undergoing illegal deforestation.

- Status: As of 11/30/23 – referred to the Committee on Finance.

H.R.8790 – Fix Our Forests Act

- Summary: Improves forest management activities on National Forest System lands, on public lands, and on Tribal lands to return habitat resilience.

- Status: As of 11/12/24 – Passed House. Received in Senate and Read twice and referred to the Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry.

- Similar Bills: H.R.3853/S.1831– Roadless Area Conservation Act of 2023; S.808 – Expediting Forest Restoration and Recovery Act of 2023

S.4370 – Tribal Forest Protection Act Amendments Act of 2024

- Summary: Amends the Tribal Forest Protection Act of 2004 to include forest restoration as well as protection and to establish a budget of $15 million per year over the course of five years.

- Status: As of 9/25/24 – Committee on Indian Affairs approved to report the amended bill to the Senate.

- Summary: Directs the Secretary of Housing and Urban Development to create a grant program for planting trees in eligible underserved areas.

- Status: As of 07/20/23 – Referred to the House Committee on Financial Services.

Not sure who represents you in congress? Follow these quick steps to find your congressional representatives and how to contact them:

- Click here and input your home address, then click the search icon.

- Under the name of the representative you want to reach, look for the section titled “Contact.”

- To make a phone call, copy the phone number provided.

- To send an email (or other form of outreach), select the blue hyperlinked word “contact.”

- This will take you to a page with different methods for reaching your representative.

To make the process as simple as possible, we’ve provided you with email and phone call templates. Simply fill in the blanks with your information and then reach out to your representatives!

Your vote means something. It’s your chance to voice your support for the people and policies you think will make a positive difference in your community and across the country.

Register to Vote

Not yet registered to vote? Get started:

It’s super easy! All you have to do is:

- Select the state or territory you live in

- Start your online voter registration

When registering, make sure you have a valid form of identification. This could be your Driver’s License, State ID, and/or Social Security Number.

Find Your Voting Location

Are you a new voter? Have you moved recently? Or maybe you just want to double check you know where you’re going? Find your voting location:

Remind Others to Vote

- Text election reminders to friends and family

- Snap that “I Voted” selfie and share it with the world (this simple act has been shown to increase voter turnout by 4.1%)

- Help others create a voting plan

- Sign up for programs like When We All Vote to help educate others on the importance of voting, important deadlines, and more

- The Issue

- Advocate

- Keep Learning

Education is the first step in building public support for the importance of our forests, both traditional and urban. Teaching people the truth about what a healthy forest ecosystem looks like and why simply planting more trees is not always the right solution are incredibly important steps to help alleviate the burden of misinformation that currently exists today.

Other, newer concepts like urban greening and forest mapping may be unfamiliar to large swaths of the population, which acts as a barrier to entry for participation in citizen science projects that increase awareness of the importance of forests and the need to protect them.

Education also needs to occur at the legislative level. Those with the power to make change should have at the very least a basic understanding of sustainable forest management to make decisions that are right for both people and the planet.

Share This Page

Help educate your network of friends, family and followers when you share this page and post about it on social media!

Explore Further

Interested in learning more about the importance of forest restoration? We’ve compiled a list of key resources to help you move forward on your learning path.

Experts

Meet the professionals fighting for forest restoration throughout the U.S.

- Alliance for the Chesapeake Bay

- American Forests

- National Forest Foundation

- Washington Conservation Action

- Our City Forest

Learning Hubs

Dive deeper into the topic with more educational tools.

- Tools, Research, Reports & Guides | American Forests

- Network Resources | Alliance for the Chesapeake Bay

- The AV Room | Conservation Northwest

- Tree Equity | Our City Forest

Other Resources

- Nonprofit Limitations

- Donate

- Volunteer

Ask any nonprofit in America (and around the world) what their greatest two challenges are, and they are very likely to say the same things: funding and capacity.

Nonprofits striving to implement and advance forest restoration throughout the U.S. and around the globe are no stranger to this. That’s why your support—be it financial or through volunteer work—makes an enormous difference. By supporting an organization with your time and/or money, you are helping to increase their impact, expand their reach, and make it easier for good to be done for our planet.

Donate to Nonprofits

Meet the vetted EarthShare Nonprofit Partners making a difference for forest restoration and donate to their cause!

- Alliance for the Chesapeake Bay | Delivering on-the-ground solutions for healthier lands, forests, and waters throughout the Mid-Atlantic

- Amazon Aid Foundation | Cultivating a cleaner gold supply chain to protect the Amazon Forest, its ecosystems, and biodiversity

- American Forests | Scaling up healthy forest restoration across North America and helping forests adapt to climate stressors

- Bird Conservancy of the Rockies | Monitoring North American tropical and montane forests critical to dozens of endemic bird specie

- Buckeye Environmental Network | Providing tools and support to mobilize communities to protect Ohio’s native public forests under threat

- Conservation Northwest | Advancing scientific research and working with partners to promote landscape-scale forest restoration

- Forest Stewardship Council | Setting standards and harnessing market demand for responsible forest management

- Friends of the Chicago River | Improving the Chicago-Calumet River system and its surrounding watershed habitat

- Greater Hells Canyon Council | Connecting and protecting wild lands and forests, waters, and species, of the Greater Hells Canyon Region

- Housatonic Valley Association | Working across the Housatonic Watershed to restore lands and forests for cleaner water

- National Forest Foundation | Restoring U.S. National Forests by promoting conservation and recreation

- Our City Forest | Transforming Silicon Valley through urban forestry, environmental education, and the power of trees

- The Phoenix Conservancy | Rehabilitating endangered ecosystems to increase resiliency and benefit diverse wildlife

- Washington Conservation Action | Ensuring timber forests are sustainably managed throughout Washington state

Attend Events & Volunteer

Want more ways to get involved? Check out events and volunteer opportunities happening online, across the country, and near you.

- Alliance for the Chesapeake Bay | Events | Volunteer | Regional (Northeast)

- American Forests | Volunteer | National

- Conservation Northwest | Volunteer | International

- Forest Stewardship Council | Events | National

- Friends of the Chicago River | Events | Volunteer | Illinois

- Greater Hells Canyon Council | Events | Volunteer | Oregon

- Housatonic Valley Association | Volunteer | New England

- National Forest Foundation | Events | Volunteer | National

- Our City Forest | Volunteer | California

- The Phoenix Conservancy | Volunteer | International

- Washington Conservation Action | Events | Volunteer | Washington

- Policy

- Education

- Support

- Bills

- Engage Congress

- Vote

The following bills supporting open spaces have been introduced in congress. Read through each bill below to learn what it’s about and its current status, then continue on to the “Engage Congress” tab to discover how to easily request your congressperson’s support for these pieces of legislation. (When looking at the bill name and number, “H.R.” stands for House of Representatives and “S” stands for Senate.)

- Summary: Prohibits the importation of products made in whole or in part from materials produced on land undergoing illegal deforestation.

- Status: As of 11/30/23 – referred to the Committee on Finance.

H.R.8790 – Fix Our Forests Act

- Summary: Improves forest management activities on National Forest System lands, on public lands, and on Tribal lands to return habitat resilience.

- Status: As of 11/12/24 – Passed House. Received in Senate and Read twice and referred to the Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry.

- Similar Bills: H.R.3853/S.1831– Roadless Area Conservation Act of 2023; S.808 – Expediting Forest Restoration and Recovery Act of 2023

S.4370 – Tribal Forest Protection Act Amendments Act of 2024

- Summary: Amends the Tribal Forest Protection Act of 2004 to include forest restoration as well as protection and to establish a budget of $15 million per year over the course of five years.

- Status: As of 9/25/24 – Committee on Indian Affairs approved to report the amended bill to the Senate.

- Summary: Directs the Secretary of Housing and Urban Development to create a grant program for planting trees in eligible underserved areas.

- Status: As of 07/20/23 – Referred to the House Committee on Financial Services.

Not sure who represents you in congress? Follow these quick steps to find your congressional representatives and how to contact them:

- Click here and input your home address, then click the search icon.

- Under the name of the representative you want to reach, look for the section titled “Contact.”

- To make a phone call, copy the phone number provided.

- To send an email (or other form of outreach), select the blue hyperlinked word “contact.”

- This will take you to a page with different methods for reaching your representative.

To make the process as simple as possible, we’ve provided you with email and phone call templates. Simply fill in the blanks with your information and then reach out to your representatives!

Your vote means something. It’s your chance to voice your support for the people and policies you think will make a positive difference in your community and across the country.

Register to Vote

Not yet registered to vote? Get started:

It’s super easy! All you have to do is:

- Select the state or territory you live in

- Start your online voter registration

When registering, make sure you have a valid form of identification. This could be your Driver’s License, State ID, and/or Social Security Number.

Find Your Voting Location

Are you a new voter? Have you moved recently? Or maybe you just want to double check you know where you’re going? Find your voting location:

Remind Others to Vote

- Text election reminders to friends and family

- Snap that “I Voted” selfie and share it with the world (this simple act has been shown to increase voter turnout by 4.1%)

- Help others create a voting plan

- Sign up for programs like When We All Vote to help educate others on the importance of voting, important deadlines, and more

- The Issue

- Advocate

- Keep Learning

Education is the first step in building public support for the importance of our forests, both traditional and urban. Teaching people the truth about what a healthy forest ecosystem looks like and why simply planting more trees is not always the right solution are incredibly important steps to help alleviate the burden of misinformation that currently exists today.

Other, newer concepts like urban greening and forest mapping may be unfamiliar to large swaths of the population, which acts as a barrier to entry for participation in citizen science projects that increase awareness of the importance of forests and the need to protect them.

Education also needs to occur at the legislative level. Those with the power to make change should have at the very least a basic understanding of sustainable forest management to make decisions that are right for both people and the planet.

Share This Page

Help educate your network of friends, family and followers when you share this page and post about it on social media!

Explore Further

Interested in learning more about the importance of forest restoration? We’ve compiled a list of key resources to help you move forward on your learning path.

Experts

Meet the professionals fighting for forest restoration throughout the U.S.

- Alliance for the Chesapeake Bay

- American Forests

- National Forest Foundation

- Washington Conservation Action

- Our City Forest

Learning Hubs

Dive deeper into the topic with more educational tools.

- Tools, Research, Reports & Guides | American Forests

- Network Resources | Alliance for the Chesapeake Bay

- The AV Room | Conservation Northwest

- Tree Equity | Our City Forest

Other Resources

- Nonprofit Limitations

- Donate

- Volunteer

Ask any nonprofit in America (and around the world) what their greatest two challenges are, and they are very likely to say the same things: funding and capacity.

Nonprofits striving to implement and advance forest restoration throughout the U.S. and around the globe are no stranger to this. That’s why your support—be it financial or through volunteer work—makes an enormous difference. By supporting an organization with your time and/or money, you are helping to increase their impact, expand their reach, and make it easier for good to be done for our planet.

Donate to Nonprofits

Meet the vetted EarthShare Nonprofit Partners making a difference for forest restoration and donate to their cause!

- Alliance for the Chesapeake Bay | Delivering on-the-ground solutions for healthier lands, forests, and waters throughout the Mid-Atlantic

- Amazon Aid Foundation | Cultivating a cleaner gold supply chain to protect the Amazon Forest, its ecosystems, and biodiversity

- American Forests | Scaling up healthy forest restoration across North America and helping forests adapt to climate stressors

- Bird Conservancy of the Rockies | Monitoring North American tropical and montane forests critical to dozens of endemic bird specie

- Buckeye Environmental Network | Providing tools and support to mobilize communities to protect Ohio’s native public forests under threat

- Conservation Northwest | Advancing scientific research and working with partners to promote landscape-scale forest restoration

- Forest Stewardship Council | Setting standards and harnessing market demand for responsible forest management

- Friends of the Chicago River | Improving the Chicago-Calumet River system and its surrounding watershed habitat

- Greater Hells Canyon Council | Connecting and protecting wild lands and forests, waters, and species, of the Greater Hells Canyon Region

- Housatonic Valley Association | Working across the Housatonic Watershed to restore lands and forests for cleaner water

- National Forest Foundation | Restoring U.S. National Forests by promoting conservation and recreation

- Our City Forest | Transforming Silicon Valley through urban forestry, environmental education, and the power of trees

- The Phoenix Conservancy | Rehabilitating endangered ecosystems to increase resiliency and benefit diverse wildlife

- Washington Conservation Action | Ensuring timber forests are sustainably managed throughout Washington state

Attend Events & Volunteer

Want more ways to get involved? Check out events and volunteer opportunities happening online, across the country, and near you.

- Alliance for the Chesapeake Bay | Events | Volunteer | Regional (Northeast)

- American Forests | Volunteer | National

- Conservation Northwest | Volunteer | International

- Forest Stewardship Council | Events | National

- Friends of the Chicago River | Events | Volunteer | Illinois

- Greater Hells Canyon Council | Events | Volunteer | Oregon

- Housatonic Valley Association | Volunteer | New England

- National Forest Foundation | Events | Volunteer | National

- Our City Forest | Volunteer | California

- The Phoenix Conservancy | Volunteer | International

- Washington Conservation Action | Events | Volunteer | Washington

Where to Start

There’s a reason the term “tree hugger” began to be associated with environmentalists… because trees are incredibly important. We all benefit from them, so we all have a responsibility—and opportunity—to protect the health of our forests, regardless of whether you live near them. Luckily, it’s simple to do.

We’ve curated a list of nonprofits doing work in the United States and around the world to restore forests. Learn more about their incredible work and show your support.

Check out these orgs!

Alliance for the Chesapeake Bay*Alliance for the Chesapeake Bay is our 30×30 Partner for forest restoration and contributed their knowledge, experiences, and on-the-ground expertise to improve accuracy and storytelling. | Delivering on-the-ground solutions for healthier lands, forests, and waters throughout the Mid-Atlantic

Amazon Aid Foundation | Cultivating a cleaner gold supply chain to protect the Amazon Forest, its ecosystems, and biodiversity

American Forests | Scaling up healthy forest restoration across North America and helping forests adapt to climate stressors

Bird Conservancy of the Rockies | Monitoring North American tropical and montane forests critical to dozens of endemic bird species

Buckeye Environmental Network | Providing tools and support to mobilize communities to protect Ohio’s native public forests under threat

Conservation Northwest | Advancing scientific research and working with partners to promote landscape-scale forest restoration

Forest Stewardship Council | Setting standards and harnessing market demand for responsible forest management

National Forest Foundation | Restoring U.S. National Forests by promoting conservation and recreation

Our City Forest | Transforming Silicon Valley through urban forestry, environmental education, and the power of trees

Washington Conservation Action | Ensuring timber forests are sustainably managed throughout Washington state

* EARTHSHARE 30×30 PARTNER

Created as part of the Mosaic 2023 Movement Infrastructure grant program

Share your thoughts on The 30×30 Project website

©2025 EarthShare. All rights reserved. EarthShare is a registered 501(c)(3) nonprofit.