The

30x30

Project

Protecting 30% to save 100%

Our planet is in trouble. The 30×30 Project isn’t the full solution, but it’s an important step to help us all understand the state of the world we live in and to ensure the health of our planet moving forward. Join us as we dive into six critical, interconnected environmental solutions that will help us achieve the 30×30 target and save the world.

30x30 Explained

The 30×30 target aims to protect at least 30% of both our global lands and seas in order to preserve critical biodiversity and ecosystems.

Core Principles of 30x30

To address 30×30 in a way that is both equitable and sustainable, solutions must be committed to the following eight principles.

Pursue a collaborative and inclusive approach to conservation. The “top down” approach doesn’t work when it comes to the environment. We must provide seats at the table for everyone—especially those disproportionately impacted by environmental issues.

Build on existing strategies, emphasizing flexible and adaptive approaches. Adapting strategies informed by past and current work will be key as we approach 2030. Initiatives for a variety of environmental approaches (like the co-benefits of sustainable agriculture and forest regeneration) lead to more flexibility.

Conserve America’s lands and waters for the benefit of all people. Everyone can and should benefit from an improved environment; not just select peoples or geographies. Solutions should do good across all boundaries, including (but certainly not limited to) country, culture, race, class, religion, tribal affiliations, gender, and sexual orientation.

Support locally led and locally designed conservation efforts. Local communities are experts on the environmental issues that impact them most. Local leaders and activists can implement solutions in a manner that’s truly valuable to their communities. These actions will have the most immediate and positive impact.

Support Tribal Nation priorities and sovereignty. Indigenous groups have lived in balance with nature for millennia. Today, many U.S. Tribal Nations lead the country in housing healthy, biodiverse habitats. With this knowledge and leadership, Tribal Nations can lead us to a healthier future.1"Indigenous Peoples: Defending an Environment for All," International Institute for Sustainable Development ≫

Pursue projects that create jobs and support healthy communities. 30x30 solutions shouldn’t overburden our economy. Instead, they should boost our communities and local economies through the creation of green jobs, new opportunities, and improved health and wellness.

Honor private property and support voluntary stewardship. Private landowners, both residential and commercial, can enact powerful protections on their own lands and waters. These efforts not only protect ecologically significant habitats, but also cultivate a sustainability-first mindset.

Use science as a guide. All decisions and 30x30 solutions should be supported by science. We should use relevant, peer reviewed data to inform the areas we prioritize. Once a solution is enacted, we can use science and data to determine how effective it is and adapt as necessary.

Solutions Library

Click below to learn more about how 30×30 goals will renew our communities and biodiversity.

Sustainable Agriculture

Achieving 30×30 by addressing our biggest source of land use

Pollinators

Achieving 30×30 by aiding our pollinators

Coral Reef Restoration

Achieving 30×30 by restoring our coral reefs

Resilient Communities

Building resilient, sustainable communities to help reach 30×30

Forest Restoration

Advancing 30×30 goals by restoring our forests

Sustainable Fisheries

Achieving 30×30 by addressing how we fish

Endangered Species Protection

Advancing 30×30 goals by preserving wildlife biodiversity

Waste Prevention

Advancing 30×30 goals by preventing waste from entering global ecosystems

Open Spaces

Advancing 30×30 goals by increasing access to natural spaces

Renewable Energy

Advancing 30×30 goals by expanding the adoption of renewable energy

The Importance of Traditional Indigenous Knowledge

Indigenous Peoples around the world have been practicing variations of these solutions for thousands of years—these are not new ideas. As the originators of these practices, Indigenous communities continue to be thought leaders, subject experts, and biodiversity stewards.1“CAP Event Highlights Partners in Indigenous-Led Conservation,” Center for American Progress ≫

We need to amplify these voices and prioritize opportunities for Indigenous leadership as we form and implement solutions to achieve our goal of 30×30.

IMAGE: JialiangGao/Wikimedia

For more than a millenium, China’s Hani people have maintained a complex, productive system of terraces to cultivate rice in rough mountain terrain. Read more on the 30×30 Sustainable Agriculture page >>>

IMAGE: Patrick Shepherd/CIFOR

Ester Sitomik discusses the central role of conservation as a member of the Kenya’s Ogiek community. Read more on the 30×30 Pollinators page >>>

IMAGE: T. Tunsch/Wikimedia

Stones mark the boundary of a Native Hawaiian ahupua’a, an ancient land management system that protects resources from the mountains to the ocean. Read more on the 30×30 Coral Reef Restoration page >>>

IMAGE: Anthony Auston/Flickr

New Zealand’s largest and oldest living tree (dating almost 2,500 years), Tane Mahuta is a focal point of Indigenous Maori efforts to protect delicate ecosystems. Read more on the 30×30 Forest Restoration page >>>

IMAGE: Natural Sciences & Engineering Research Council of Canada/YouTube

The Heiltsuk First Nation community still maintains Indigenous fishing practices along of coastal British Columbia. Read more on the 30×30 Sustainable Fisheries page >>>

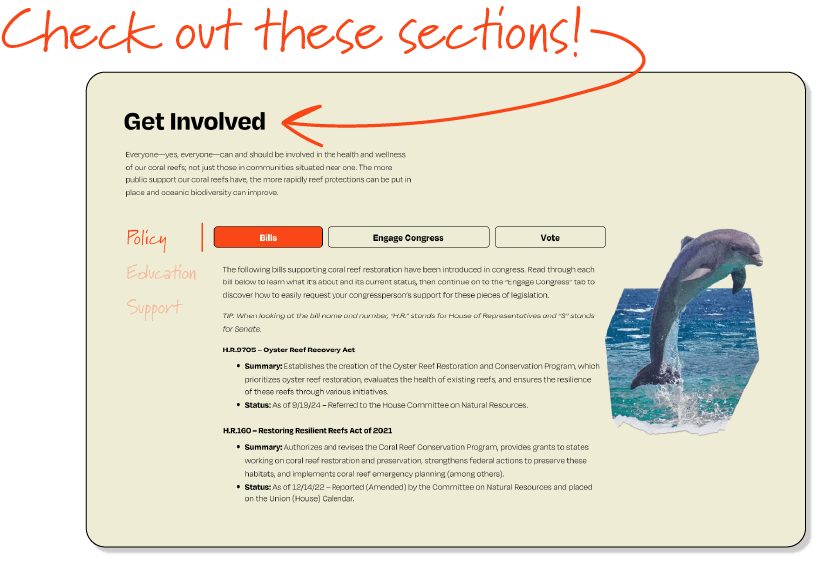

How You Can Get Involved

Learn. Support. Share. Contribute to 30×30 solutions in three simple steps!

Learn About the Solutions

Learn About the Solutions

Support Participating Nonprofits

Support Participating Nonprofits

Share Your Knowledge

Share Your Knowledge

The Big Questions

Environmental issues offen leave us with more questions than answers . . . But confronting them head-on will lead us to a stronger, healthier future.

When talking about the 30×30 target, “land” is any terrestrial (“land-based”) habitat that is critical for conservation and biodiversity. This can include all land-based biomes, from the arctic tundra, to rainforests, to deserts, both hot and cold. (Yes, there are polar deserts!)2“Life in the Extreme: Polar Deserts,” NASA ≫

To achieve the goal of 30% of land conservation, we must prioritize land that has not been previously developed (a.k.a. “untouched” land). Once these ecologically important regions have been protected, we can move on to improving lands that have already been developed in some way.

“Water,” when used in reference to the 30×30 target, is specifically referring to freshwaters and marine waters that are critical for conservation and biodiversity. Ocean areas closest to land are often the most ecologically important due to the ecosystems they support. They’re also the most likely to be impacted by humans.

It’s important that we protect waters that play a significant role in marine and freshwater ecosystems—as well as all land ecosystems—and which are most at risk of harm.

In order to identify the lands and waters that need protection (and to implement proper solutions), we must consider and address the following questions:

- Is the land/water important for biodiversity?

- Does the land/water contribute to people in some way?

- Is the land/water ecologically representative?

- Does the land/water have well-connected systems?

- Is the land/water being effectively managed?

- Are the land/water protections equitably established?

- Are the lands/waters integrated into wider landscapes/seascapes?

The 30×30 target is certainly an expensive goal, but not as expensive as you might think. Experts estimate that we can expect to spend anywhere from $100 billion USD to $178 billion USD per year globally. (For some perspective, it’s roughly the same as two months’ worth of global oil industry subsidies.) It’s a large number, sure, but it’s doable. The money is there; we must prioritize it.3“Best Practice in Delivering the 30×30 Target,” The Nature Conservancy ≫

The 30×30 target aims to conserve 30% of lands and waters that are wild, undeveloped, and ecologically important. Research suggests that 26% of the planet’s surface is still relatively wild, while 56% is considered to have low human impact. So, yes, there is certainly enough space—both land and water—to make a significant impact.4“Best Practice in Delivering the 30×30 Target,” The Nature Conservancy ≫; “Global human influence maps reveal clear opportunities in conserving Earth’s remaining intact terrestrial ecosystems,” Global Change Biology ≫

But how do we identify where to start? The 30×30 target largely focuses on officially-recognized protected areas, marine protected areas (MPAs), and other effective conservation measures (OECMs). These various protected regions are highly regulated with restrictions to deter negative human impact. To qualify as part of the global 30%, the identified lands and waters must meet multiple criteria, including being in a fully natural or near-natural state. Some lands and waters will need to go through restoration as part of their protection and management.

To accurately initiate these protections will, in many places, require partnerships with Indigenous groups and local communities who are already familiar with the region—many of whom already steward significant biodiverse lands.

At the 2022 U.N. Biodiversity Conference, 196 countries ratified the 30×30 target and its much larger parent treaty, the Global Biodiversity Framework. Only two countries didn’t sign: the Vatican and the United States. Since then, the U.S. has pledged billions of dollars toward climate and biodiversity support.5“Progress Report on President Biden’s Climate Finance Pledge,” U.S. Department of State ≫

But who is responsible for enacting solutions?

Each country must address its own ecologically significant 30% of lands and waters. However, some countries are home to more globally significant ecosystems than others. In this case, larger and more financially and industrially developed countries must step up to the plate and assist—through funding and resources—in the implementation of proper programming and protections.

Who must foot the bill for the 30×30 target? For starters, the countries who have an outsized negative environmental impact compared to other smaller, less industrious and/or wealthy nations. (United States, looking at you!)

Global governments that signed the Convention of Biological Diversity (CBD) and the Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF)—more than 190 countries around the world—also agreed to preserve their own individual protections for 30% of their lands and waters. This includes contributing financially to solutions via taxes and fees, a user-pays approachs, private and international donors, and restructured debts.

Recently, the United States provided $91 million in funding through one of EarthShare’s Partner organizations, National Fish and Wildlife Foundation (NFWF) and their America the Beautiful program.6“America the Beautiful Challenge,” National Fish and Wildlife Foundation ≫

YES! 30×30 is a scientifically backed target, which means it’s certainly achievable, but it requires commitment at all levels of the government and full public support. We need to come together—and quickly—to make it happen.

One major initial obstacle is education. If this is your first time hearing about 30×30 or exploring what this target will take to achieve, you are not alone. A huge portion of the global population—especially those who aren’t involved in the environmental sector—have no idea what 30×30 is or what it means. There are probably others in your life who haven’t heard of it either!

The more we can share this knowledge and inspire action, the more people who are pushing for positive change, and the more likely we are to build momentum and achieve these goals.

Definitely not. Achieving 30% by 2030 is only the beginning. Climate scientists are already calling for 50% by 2050 to better support the ecosystems we rely on. But we must start somewhere, and the foundations we put into place by 2030 will make these larger land and water protections possible.

In the meantime, we must ensure that, although we’re protecting 30% of ecologically representative lands and waters, the remaining 70% that is unprotected doesn’t suffer. After all, our planet will be in far worse shape if we continue to allow our natural world to be overly burdened by fossil fuels, pollution, deforestation, and the like. Our approach must be balanced, and we need to keep our eyes on the big picture as we implement solutions both now and in the future.

Created as part of the Mosaic 2023 Movement Infrastructure grant program

Share your thoughts on The 30×30 Project website

©2025 EarthShare. All rights reserved. EarthShare is a registered 501(c)(3) nonprofit.